A Guide to Archaeological Illustration

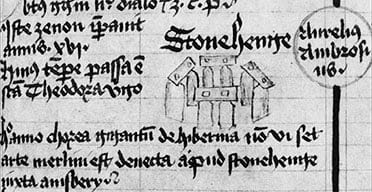

As the 2018 season of Dig Berkeley draws to a close, we are taking a look at some of the techniques in archaeology that don't often get the spotlight, but are important in the understanding and recording of our finds. One such technique is archaeological illustration. There is evidence that archaeological illustration has been utilised since the medieval period, with archaeological artefacts and sites being recorded through drawing such as a 14th century interpretation of Stonehenge, below. Archaeological illustrations became especially common in Europe during the Renaissance; topographical illustrations featuring interesting parts of the landscape were commonly created, including earthworks or mounds of archaeological interest. Many of these early illustrations were inaccurate, sometimes drawn based on verbal descriptions or brief observations, and were often not recognised as specifically archaeological features. One of the first measured and planned illustrations of archaeological buildings were published in The Antiquities of Athens, by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett (Adkins and Adkins, 1989).

The principles of archaeological illustrations are to keep a detailed record of an artefact or monument, and to provide a representation which other archaeologists who do not have access to the artefact can use for further analysis. Collating drawings of different types and forms of artefacts, for example different types of pottery, can be used by archaeologists to aid in typological dating (dating an object by its style or design). Because of this, it is important that drawings are as technical as possible, well measured, and show the play of light and shadow on the artefact to give a three dimensional effect.

Despite great strides having been made in the quality of photography in the last 50 years, illustration is still a useful archaeological technique. Even though photographs show a clear representation of an object, they do not always show relevant details that can be lost in a photograph but caught by the eye of an illustrator, like areas of wear on leather or metal, the effect of shadows and light on an object, and texture. In addition, illustrations can incorporate details from many different angles into one drawing, rather than needing to take a series of photographs to show different angles. Details obscured by coloured areas of an artefacts are also more visible in illustrations, which are black and white as standard. Often, both photographs and illustrations are used alongside each other in publications, so both colours and details are visible to readers.

While archaeological illustrations have traditionally been created by hired artists and painters, today most archaeologists should be able to draw an archaeological illustration to some degree without having to outsource this role. There are special rules that accompany archaeological illustrating today. A typical illustration will require drawing boards, rulers, lamps, drafting film, and HB pencils or a high quality black ink pen. Illustrations of certain sites or finds may need extra equipment such as tools to measure pot rims or magnifying glasses for small, highly detailed objects. Lighting is also important in an illustration; archaeologists are taught to remember that the light always comes from the top left corner. It also should be drawn to a sensible scale, or even 1:1 in case of a very small object. With technology rapidly improving, archaeological illustration is developing as well. Today's archaeologists have begun to utilise digital drawing tablets that allow them to apply pressure on the screen to create different thicknesses of lines and shade effects.

The practice of archaeological illustration should not be confused with reconstruction illustrations, such as those of Catalhoyuk or the illustrations of John G. Swogger. Reconstruction drawings are used to give an idea of how certain monuments, sites or artefacts would have looked when in use, rather than an accurate representation of what they look like now.

At Dig Berkeley, second-year student Julia has been working hard on some fantastic illustrations of artefacts included in our exhibition.

When asked why she chose these particular artefacts, she said that she wanted to draw the Berkeley family glass seal because its details are hard to see when photographed. She also chose the harness pendant and the strap end, because they were beautifully detailed small objects, and enjoyable to draw. All of the drawings above are drawn at 1:1 scale.

|

| Stonehenge from the 14th century Scala Mundi chronicles (Kennedy, 2006) |

The principles of archaeological illustrations are to keep a detailed record of an artefact or monument, and to provide a representation which other archaeologists who do not have access to the artefact can use for further analysis. Collating drawings of different types and forms of artefacts, for example different types of pottery, can be used by archaeologists to aid in typological dating (dating an object by its style or design). Because of this, it is important that drawings are as technical as possible, well measured, and show the play of light and shadow on the artefact to give a three dimensional effect.

Despite great strides having been made in the quality of photography in the last 50 years, illustration is still a useful archaeological technique. Even though photographs show a clear representation of an object, they do not always show relevant details that can be lost in a photograph but caught by the eye of an illustrator, like areas of wear on leather or metal, the effect of shadows and light on an object, and texture. In addition, illustrations can incorporate details from many different angles into one drawing, rather than needing to take a series of photographs to show different angles. Details obscured by coloured areas of an artefacts are also more visible in illustrations, which are black and white as standard. Often, both photographs and illustrations are used alongside each other in publications, so both colours and details are visible to readers.

While archaeological illustrations have traditionally been created by hired artists and painters, today most archaeologists should be able to draw an archaeological illustration to some degree without having to outsource this role. There are special rules that accompany archaeological illustrating today. A typical illustration will require drawing boards, rulers, lamps, drafting film, and HB pencils or a high quality black ink pen. Illustrations of certain sites or finds may need extra equipment such as tools to measure pot rims or magnifying glasses for small, highly detailed objects. Lighting is also important in an illustration; archaeologists are taught to remember that the light always comes from the top left corner. It also should be drawn to a sensible scale, or even 1:1 in case of a very small object. With technology rapidly improving, archaeological illustration is developing as well. Today's archaeologists have begun to utilise digital drawing tablets that allow them to apply pressure on the screen to create different thicknesses of lines and shade effects.

The practice of archaeological illustration should not be confused with reconstruction illustrations, such as those of Catalhoyuk or the illustrations of John G. Swogger. Reconstruction drawings are used to give an idea of how certain monuments, sites or artefacts would have looked when in use, rather than an accurate representation of what they look like now.

At Dig Berkeley, second-year student Julia has been working hard on some fantastic illustrations of artefacts included in our exhibition.

She has also previously drawn a fantastic dagger from the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery:

When asked why she chose these particular artefacts, she said that she wanted to draw the Berkeley family glass seal because its details are hard to see when photographed. She also chose the harness pendant and the strap end, because they were beautifully detailed small objects, and enjoyable to draw. All of the drawings above are drawn at 1:1 scale.

Bibliography

Adkins L. and Adkins R. 1989. Archaeological Illustration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, M. 2006. Early Sketch of Stonehenge Found. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/nov/27/arts.artsnews.

Kennedy, M. 2006. Early Sketch of Stonehenge Found. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/nov/27/arts.artsnews.

Comments

Post a Comment